|

| Pilgrims waited ridiculously patiently for hours to attend the Papal Mass, |

The Black Zone is what the City of Philadelphia chose to call the secure area on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway where Pope Francis would, among other things, celebrate an open-air mass for up to a projected million pilgrims. They apparently called it the Black Zone because, when first outlined on a map, they used a black marker.

That loud sound you just heard: all our colleagues in marketing, advertising, and public relations simultaneously slapping their foreheads in disbelief.

But surprisingly, a missed marketing opportunity is not what I’m going to focus on in this post. The reason the name was so inappropriate? The pilgrims inside the Black Zone were the least psychologically dark people I have ever seen – and there were over eight hundred thousand of them packed onto the temporarily car-free Parkway.

|

| Still waiting patiently |

To the surprise and dismay of our upscale restaurants, these weren’t free-spending tourists. They were pilgrims, and many had made sacrifices to get here; the family that drove thousands of miles from Argentina, the kids who worked all summer to raise the money for their family trip, the three ladies who spent 16 hours on the bus from Indiana... everyone had a story.

All on a pilgrimage to see their Pope, they were happy to be here, and they were – to use a word I haven’t used since the 1960s – mellow.

How mellow? After dealing with crowds of nearly a million over the long weekend, the police announced they made only three event-related arrests.

Three.

Three.

So what made this crowd unique? The Parkway has hosted huge crowds before – everything from concerts to fireworks to festivals—July 4th is the big one here. Why was this crowd so casually indifferent to the social, racial, and class distinctions that usually divide us?

The answer lies not in the Catholic faith, but in the larger question: why people choose to join an organized religion in the first place.

It was long thought that those who volunteer their time for church activities are those with the strongest belief. That assumption turned out not to be true.

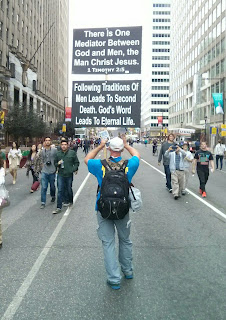

|

| Fundamentalist Christian trying to convince Catholic Pilgrims of the error of their ways. Yep. 1 Timothy 2:5 ought to do it. |

Church authorities usually cite three principal motives for joining religious groups: Belief, Behavior, and Belonging, although they may prioritize them differently.

Most Christian churches put believing first – they think people join to validate their faith. That’s why certain Christian sects punctuate their sermons with Biblical quotes. Jews and Muslims, on the other hand, traditionally give first priority to stressing behavior as the pathway to stronger belief.

There has been a lot of research on this question over the past two decades. And the evidence is now clear: when it comes to belief systems, behavior and beliefs are outcomes of belonging, not the reverse.

We join first to belong, and a strong sense of belonging affects our behavior and beliefs.

That shouldn’t be surprising. As social beings, we all exhibit a compelling preference to be among people like ourselves. We don’t do well on our own, which is why school shooters and serial killers are inevitably described as “loners.”

We not only want to be with others, we need to be with others. But we don’t want to be with just anybody. This tendency to associate and bond with others similar to ourselves is called homophily or affinity.

The beauty of a belief system is that people don’t have to look like you – they simply have to share the same values. Thus the apparent blindness to race, class, and social markers of the Parkway pilgrims.

The days when the priest told the congregation to pray to save their immortal souls are over. This Pope asked the congregants to pray for him.

Today belief and behavior are recognized as outcomes of a social bonding process. It turns out that people don’t leave their church because they no longer believe. They leave when they feel they no longer belong.

In the marketing world we recognize that brand loyalty can disappear when the manufacturer changes the product so much that the values customers originally saw in it can no longer be recognized. Vatican II started the first exodus when they changed the structure of the mass so much that it no longer evoked the rituals and traditions so central to belonging. The child molestation scandals and cover-up sparked another mass exit.

These people didn’t lose their faith, they just lost their sense of belonging. I know, because I talked to many people from both groups on the parkway while they waited for the papal mass to begin. Like I said, everyone had a story.

As social beings, shared rituals and traditions are central to reinforcing our sense of belonging, no matter what the group. For example, colleges and universities with strong and deep rituals and traditions have the most loyal and supportive alumni. My old Catholic high school, which was big on rituals and traditions, has a larger and more loyal alumni organization than many universities. Belonging is believing.

Rituals also drive customer loyalty for products. Do I have to even explain Disney? It’s the gold standard for a values-based company.

Coca-Cola, like Disney, is another values-based company. Their advertising traditionally has been based on family events and holidays—high values-based cohesive moments, and basic to memory. Coca-Cola has one of—if not the—highest levels of brand loyalty in the world.

|

| Coca Cola ads defined what Santa looked like in the 1940s and 50s. |

Coke drinkers don’t drink Pepsi, and Pepsi drinkers don’t drink Coke. Most people cut back or stop drinking carbonated soft drinks altogether around age 50. But research shows that brand loyalty remains strong even among people who no longer drink the product!

For my generation, Coke advertising pretty much defined what Santa Claus looked like. That left Pepsi and other cola brands to focus their advertising on youth, a key demographic but a diverse and proximity-driven audience with lower rates of engagement and community.

And as the ultimate example, you’ve probably heard of the Philadelphia cheesesteak, considered the city’s signature sandwich.

A few blocks from our home in South Philadelphia are two famous cheesesteak takeout joints, Pat’s and Geno’s, each with legions of loyalists. And the basis of that loyalty is that the “best” place is the one your family first took you to.

Cheesesteaks are a social food, they are a food designed to celebrate - and you don’t celebrate alone. You go there in groups, where years of tradition and ritual made their mark on the believers.

In Philly, cheesesteaks are not just food - they are a belief system.

Now you must understand, these places have a particularly South Philly style of rivalry. They are right across the street from each other. They use the same meat, the same ingredients, the same bread, the same equipment, the same cooking style - and whenever one shop is extremely busy, some of the employees of the other will walk across the street to help out.

They’ve been doing this for years. There is no earthly way you can tell the difference between a cheesesteak from Pat’s and one from Geno’s. You couldn’t even do it with a laboratory analysis.

But you could never, ever, convince their customers of that. Both groups believe that their choice is the best, and they demonstrate that belief, over and over again, by standing in long lines rather than cross the street to the less busy joint to buy the exact same sandwich.

Whether it is a religion, a theme park, a product, a university, or a cheesesteak, it’s the feeling of belonging that inspires strong belief and loyalty, not the other way around.

|

| Source: Flickr user Yuri Long |